Unexpected Sadness

Apr 22

/

Dr Sula Windgassen

How do you feel about feeling sad? It makes sense that you might feel averse to sadness. Not many people would choose to feel sad after all. You brain may very well add layers of understanding to this aversion in the form of narratives or workarounds:

It is not ok to feel sad for long. It is burdensome to feel sad in public. You can cut sadness short by being busy.

Those kinds of things. Your brain is very obliging – if it senses something is 'not good' it will find ways to warn you of that and avoid it without you having to have much in the way of a conscious thought. There is a downside to this, however. And that is that your autopilot mode can kick in wherever sadness is near, meaning that you don't get much of a chance to feel sad and to process sadness.

Sadness itself is not bad for your health. But the suppression or constant diversion of sadness can cause issues.

Sadness sprung itself on me (and everyone else)

The weekend past, I was doing some meditation (meditation with horses – I'll talk about this another time) in the most beautiful setting, on a sunny spring day, birds singing, horses smelling that sweet horsey scent, hope in the air. I felt so content and calm. If I would have been using the nervous system thermometer chart, I would have put myself right in the green spot. And then I felt the stirrings of another emotion bubbling in amongst the contentment, happiness, gratitude and calm. It was unmistakably sadness. I felt it in my chest and belly and my eyes had that stinging feeling without a single tear having dropped.

The sadness jostled in amongst the other feelings rather than pushing them out. They were all there together. And yet the sadness was strong. It felt important. It somehow felt beautiful although there was not a clear narrative as to why it was there.

When my group and I came to sit back down I was faced with considerations: do I share what I felt, when all others appeared so peaceful? Do I share when I am the professional senior amongst this group of colleagues? Do I share when I can't fully know what this sadness is in relation to right now although I can guess?

I decided I would share. And I was glad I did. It turns out others had felt similar surfacing of sadness.

Later when we collectively processed we talked about why it may have been that this was such a broadly shared experience when all of us were enjoying ourselves, were feeling relaxed and connected.

Safe to feel sad

The conclusion we came to was that we had made it safe for our brains and bodies more broadly to feel sad. We were in a serene setting, with safe others who we felt connected with and we can created the stillness to allow whatever was there to come up. When I do Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy with people, we are creating the right environment and stimulation for the brain to turn toward what is unprocessed. Although this context was very different to EMDR it had resulted in the same safeness. And from this place of trust – if I can call it that – our bodies spoke to us without narrative and just with pure emotion. Perhaps that is what felt so beautiful. To honour the sadness that was there because the root of the sadness was/is not completely solvable. It is not something that 'gets fixed' necessarily.

When I think about the people I have worked with, whose lives have been vastly changed by illness, trauma and life circumstances, it feels inhumane to encourage them to simply stop feeling sad. There are grave injustices, losses, struggles that deserve to be acknowledged, to be grieved. That process is not necessarily linear. And yet that doesn't mean that you have to feel that sadness day in, day out, moment to moment. No. What this experiences reminded me, was that our sadness is much better contained by allowing ourselves to feel it sometimes. To pull it in and offer ourselves compassion and warmth as we do. This isn't the same as “dwelling” or ruminating, which are very thought-based activities. This is about feeling. Something, that unless modelled to us, is hard to grasp.

I find that when I start to explore this process with clients, they find it so nebulous.

“But how do I feel sad? What if I don't stop?”

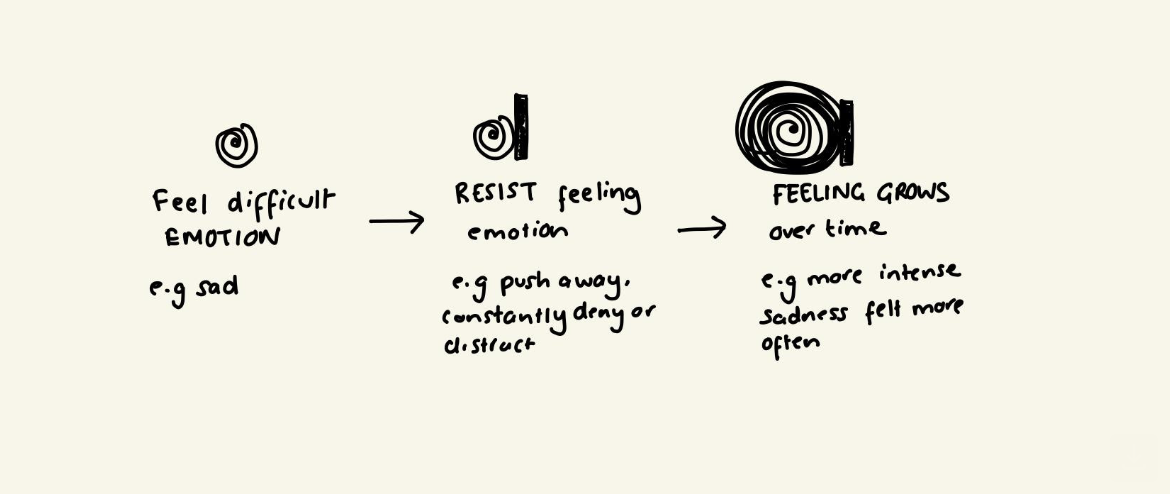

There is fear here and to that end, we have to reduce the fear around sadness in order to allow ourselves to feel it. Studies looking at what happens if we shove away feelings like sadness or try to tell ourselves that there is no point in feeling it have shown that this ends up heightening the unpleasant emotion (such as sadness) over time [1]. What this means is, if you feel a difficult emotion and you protest it repeatedly, avoiding making space for it, it grows with potentially huge impact on your mood state and health. Certainly this is reflective of what I see clinically.

It is also in line with research showing that emotional non-expression and suppression increases physiological reactivity in the body [2,3].

Benefits of feeling sad with permission

I'll be honest, I've opened many a tab exploring many a study on this subject and the results are compelling: allowing yourself to feel sad (or any difficult emotion) is healing physically as well as emotionally [4,5, 6]. In a study of a randomly picked bunch of people from the community, researchers found a clear pattern between the ability to express sadness healthily and heart rate variability (a proxy indicator of autonomic nervous system flexibility). Those that were more able to express sadness, had healthier heart rate variability (and therefore nervous system health) [5]. Another study found that the more individuals valued experiences of difficult emotions, the less their experiences of difficult emotions day to day had an impact on their physical health and psychological wellbeing [6]. The results of this study really stood out to me. To bring it to life a bit, this means that if you encounter sadness in your day (or it could be feeling angry or another typically difficult emotion) and you value that in some way – maybe just by allowing yourself to be authentic, or feeling the release of feeling it, or by giving yourself permission to process something – you are less likely to have health complaints or increases in symptom severity, etc, than if you were to try and shove it away and resist it. I think this is truly remarkable to have this empirically demonstrated. Although I concede, the practice of this is not necessarily straight forward…

Putting this in practice

There are so many directions you can go with this. But I am a fan of learning by trying out experientially. So I made a small guided sadness audio, which is designed to help your brain and body feel safer in sadness. Whether or not you identify with feeling sad, you may find that this opens up a lot more avenues for emotional regulation for you. I made it short and I made it light touch deliberately so that it is not too outfacing.

If you would like to try it out, I have inked it below.

(image of audio)

You may like to use the following prompts to reflect on after you do it:

How comfortable did it feel to feel sad?

If it was not very comfortable, why not?

How connected to yourself did you feel when you did the exercise?

Was there a way you could have been more gentle and patient? What would this look like?

I'll leave it there.

Remember, if you ever find yourself wanting to go deeper, I host the Body Mind Connect community and every Wednesday evening (7.30pm) we convene on zoom to practice and reflect together. It is a truly wonderful safe space, with a group of people committed to nurturing the mind-body connection to improve mental and physical health.

I ended up making more space for my sadness as it felt important and the rest of my week felt lighter and more aligned with my purpose and passion for it. I thought I was good at feeling sad, but sometimes the brain shortcuts kick in without you realising and you need that extra prompt. I'm glad the horses did that for me and I hope maybe this can be a gentle one for you, should you need it.

Join our mailing list to read more

If you would like to get the latest blogs directly to your inbox, please sign-up to our mailing list below.

Thank you!

About Dr Sula Windgassen, PhD

Dr Sula is a Health Psychologist, Cognitive Behavioural Therapist, Eye Movement Desensitisation & Reprocessing (EMDR) Therapist and Mindfulness Teacher. Trained at King's College London & publishing papers on the use of psychology to improve health and whole-person wellbeing.

Featured links

Copyright © 2025