In this blog, I will explain the science (and biology!) behind the mind-body pathways, and how that make it possible for you to influence your physiology. This is an important factor of why CBT may have been recommended to you.

Why would this happen, what to consider and what to do?

As a health psychologist and cognitive behavioural therapist, my clients are generally people who have been experiencing ongoing health issues. Many of them have come to me after their own research but some have been referred after a doctor or healthcare professional has suggested it. When I worked in the NHS, providing free therapy for people at various stages in their journey, a lot of the referrals I got from doctors and GPs were met with resistance from the patient. And I could well understand why.

These people had been dealing with very real, physical symptoms having a huge impact on all aspects of their life and were seeking physical remedies. Often when they were going to the doctor they were hoping for clarity, more options for definitive treatments and reassurance that things would improve. At the point the doctors were suggesting cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), there seemed to be limited other options or perhaps even no obvious other medical treatment options. The suggestion of therapy would seem to confirm the idea that things wouldn’t get any better and ‘you just need to learn how to live with it’.

For others, the suggestion of therapy coincided with discussions about how stress and anxiety made symptoms worse. Many of the patients I would see who’d had this discussed with them told me in different ways that they felt like doctors were telling them that their symptoms weren’t real and it was all in their heads.

It stood to reason that the prospect of CBT wasn’t filling the people coming into my therapy room with a lot of hope. So much so that sometimes as many as half of the sessions I could offer these people were taken up with me explaining why these sessions could not only make things feel a lot more hopeful, life richer and more full of options, but also potentially reduce symptoms. To understand this, people needed to be informed about how psychological experiences interact with physical processes in the body. That there is a constant two-way loop between psychology and biology and that where we can’t always influence the biological directly, there is scope for doing so indirectly by working with our psychological experiences.

You were raised in a society that socialised you to a ‘biomedical’ view of health. That is that human illnesses and ailments are due to discrete biological dysfunctions, anomalies or injuries that can be rectified by specific medical treatments targeting those issues. From a biomedical view, humans are very much seen as a sum of their parts and effectiveness of treatment is worked out on averages, often failing to account for important individual differences.

For example, a lot of modern medical knowledge has been accumulated from decades of research that excluded women as subjects as women only legally had to be included in research trials in 1993 [1]. This means that when treatment isn’t as effective on women than men, or comes with additional side effects, there is not much the medical system will do or say about this. A shrug of the shoulders ‘it should work’. This can make it feel like you, as the patient are failing. A biomedical system operates on a population approach to health, often failing to take into account the individual experience [2]. This is very much reflected in doctor-patient communication issues and the way that patients are often made to feel dismissed and unheard [3].

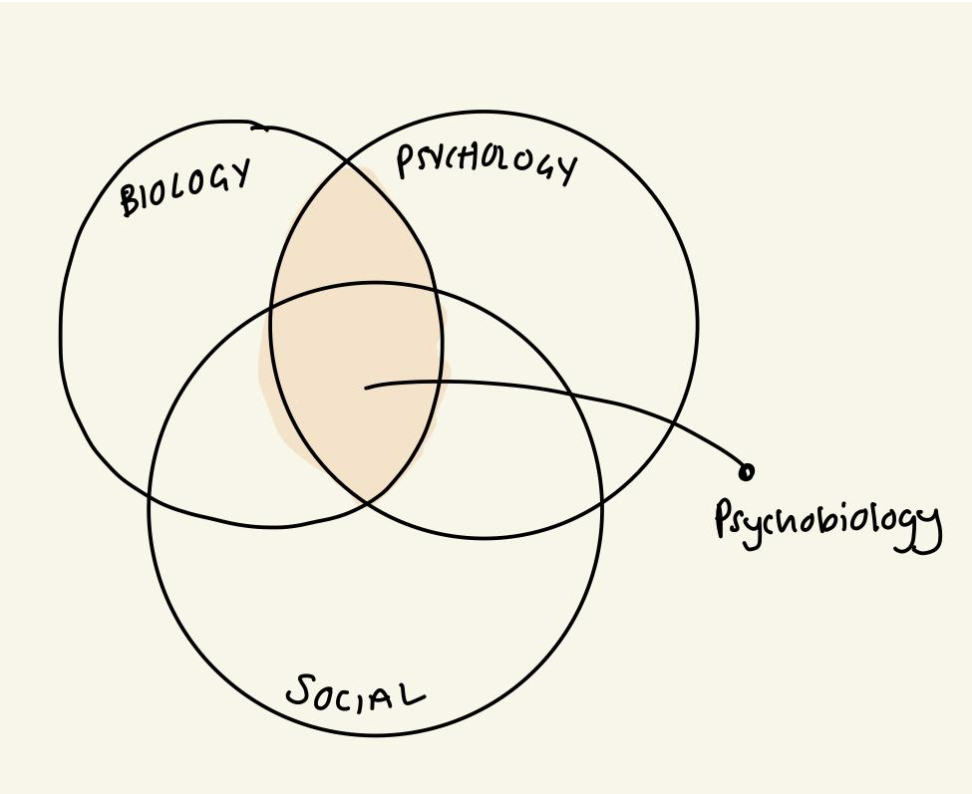

The biomedical approach is still very much the prevailing approach, despite the fact that there is a consensus that an alternative approach is more integrated, ethical and effective. This alternative view of health is called a ‘biopsychosocial approach’. This combines biology, psychology and social or environmental together, demonstrated how interacted these aspects of our experience are.

Let’s take the example of having an inflammatory condition like inflammatory bowel disease. Biologically, there is elevated inflammation which is impacting tissue in the gut and changing how the gut is functioning as well as how the immune system is responding. From a biomedical view, you simply treat the inflammation with biologics (depending on disease progression) and keep the immune system in check this way. Theoretically this stops symptoms of IBD and deterioration of health. However, for many it is not quite so simple. Lots of people with IBD also have irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) meaning that their gut is not functioning as usual and changing bowel patterns and pain [4]. Many of my clients with IBD also feel a lot of shame about symptoms and fear about how uncontrollable things have been and may be again. Here we see the overlap between biology and psychology. This is a two-way interaction. The biological effects of inflammation have caused symptoms creating psychological discomfort, but in turn this psychological discomfort is creating biological changes. The brain is processing things differently, being more alert -for example- to the presence or absence of toilets. The nervous system is more reactive, experiencing stress as more threatening with changed secretions of certain neurotransmitters and hormones. This in turn can make it harder to relax, meaning that the psychological experience is further impacted. This two-way interaction between psychology and biology is called ‘psychobiology’. Psychobiological processes also determine how social experiences influence biological changes in the body.

Research shows that experiences of, or even anticipation of, social rejection or hostility, activate areas in your brain that process physical pain (anterior cingulate cortex and insular) [5]. These social experiences therefore affect your psychobiology, often meaning you feel something emotionally (e.g. embarrassment, worry, fear, sadness) and you have some kind of physical experience (e.g. elevated pain, gut symptoms, fatigue).

The ongoing interaction between biology and psychology is underpinned by multiple bodily systems and processes, including some very complex pathways. It is useful to have an idea of some key ‘mind body pathways’

- Brain, nervous system and nerves

- Autonomic nervous system

- Enteric nervous system

- Regulatory systems (‘allostatic systems’ including your immune system)

- Biochemistry and neurochemistry

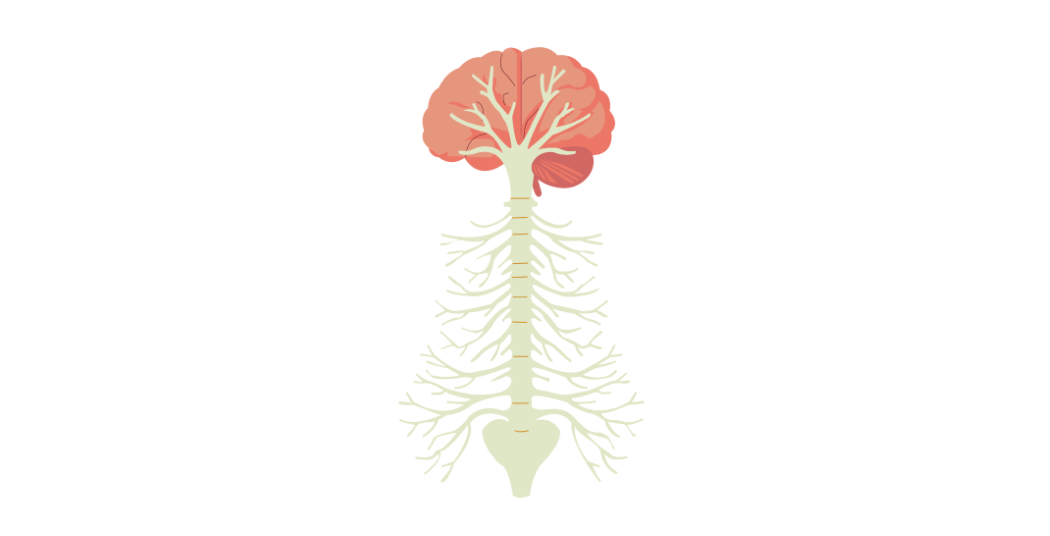

Brain, nervous system and nerves

Your brain is the control centre for your entire body, from basic functions that keep you alive like breathing and sleeping, to complex things that keep you interacting and developing like analytical thought. Different areas of the brain have what you can think of as specialisms that have a role in particular processes. For example, the amygdala has a big role in emotional processing and threat detection. However, the brain is integrated, so activity in one region of the brain, will be coordinated across other areas of the brain and not just that, with the body too. This is where the spinal cord and nerves come in. Your brain is connected to the rest of your body by the spinal cord and a network of nerves, the longest of which is the vagus nerve spanning around 80cm. These nerves and the spinal cord relay activity in the brain to and from the rest of the body.

When you have a thought, there is corresponding electrical activation in the brain. This can lead to further activation in other parts of the brain. For example, if you have a worrying thought about a symptom, that might cause the amygdala to activate, detecting threat. And such brain activation can transmit down to the body through the nerve network and biochemical signals (more on this in a moment).

Autonomic nervous system

You may have heard of the fight/flight/freeze response. This is the quick fire response system your body has to deal with immediate demands, stressors or threats. There are two branches of the autonomic nervous system: the sympathetic nervous system (fight or flight) and the parasympathetic nervous system. The two work together to help you quickly activate to meet demands and come back to a balance once demands or threats are over. The parasympathetic nervous system is innervated by the vagus nerve.

When your brain perceives demands or stressors (e.g. work or physical symptoms) it activates the sympathetic nervous system, so that you can access energy you need to mobilise and ‘fight’. This is why you may feel agitated, have a racing mind and be unable to relax when you have a lot going on. Ideally, this experience is physically balanced out by your parasympathetic nervous system when demands are less, bringing your body back to a balance. However, sometimes, your parasympathetic system can stay activated for too long or too strong, meaning that you lack energy, mobility or motivation to do what you need to do [6].

Your social and psychological experiences have a big impact on the activity of your autonomic nervous system and the balance between the sympathetic nervous system and parasympathetic nervous system. Too much stimulation can cause hyperactivity of either system, with differing effects on health. Too little stimulation can also cause insufficient activation – generally of the sympathetic nervosu system, which results in parasympathetic over-activation (also termed ‘vagal overactivity’).

If you are depleted by physical symptoms but have high expectations on you at work or home, then this will have a big impact on autonomic activation, with follow on impact on your physical experience, creating a psychobiological loop.

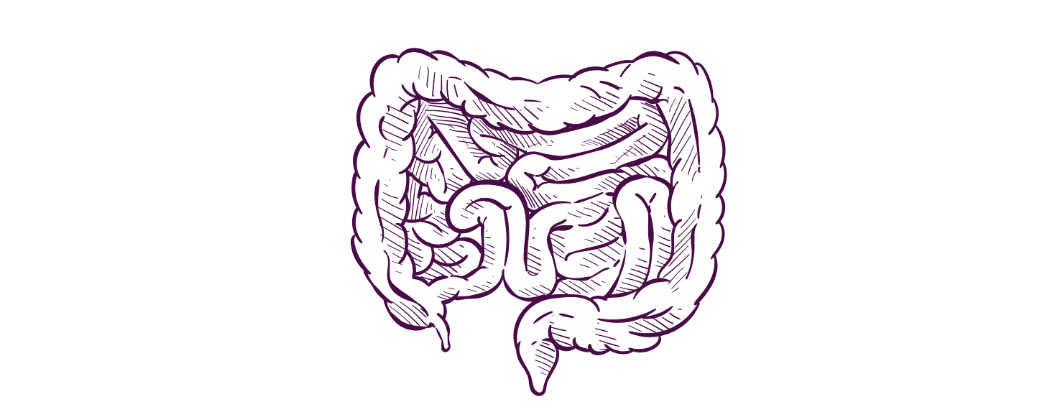

Enteric nervous system

This is known as the ‘second brain’ and it is the network of neurons (nerve cells) that live in the gut from the lower third of the oesophagus, through to the stomach, small and large intestine right down to the anus. These cells can act largely independently from the brain unlike most other organs in the body, meaning that the brain gets a lot of information up from the gut whether it asks for it or not. The gut-brain axis is two-way communication between the enteric nervous system and the central nervous system.

Although in its relative infancy in research, there is compelling data to suggest that processes in the gut are impacted and impact your mood and emotion regulation [7]. Whether or not you are experiencing gut issues, this is a significant reflection of just how interconnected your biology and psychology are.

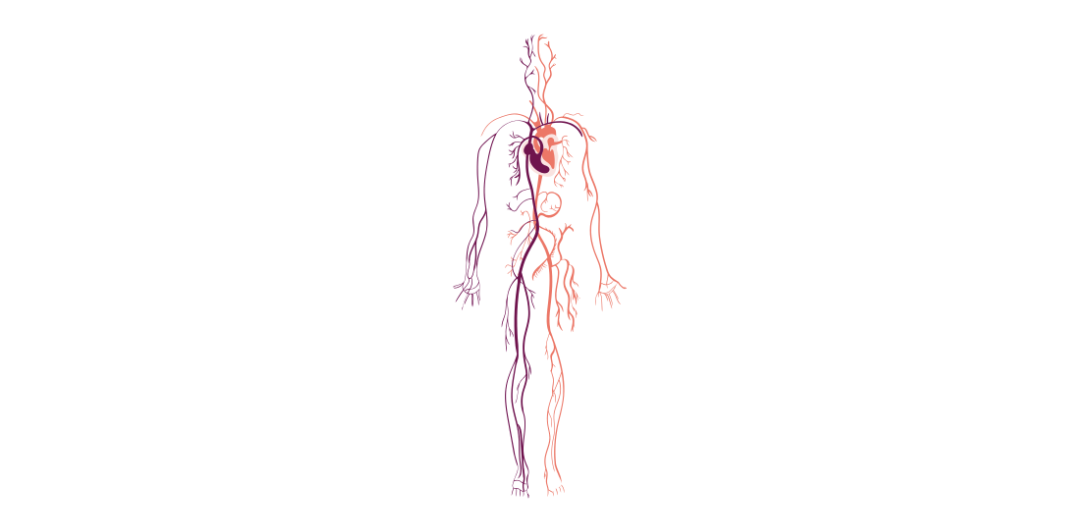

Regulatory systems (‘allostatic systems’ including your immune system)

To maintain your health and overall wellbeing your body has to keep multiple biological processes in balance. Maintaining this balance is called ‘homeostasis’. You have four primary ‘regulatory systems’ that work together to keep things balancing (including your autonomic nervous system).

They are your:

- Immune system

- Cardiovascular system

- Metabolic system

- Neuroendocrine system

Each of these systems are impacted by what you think, feel and do, while also having an effect on what you think, feel and do. For example, if you exercise regularly, this impacts your cardiovascular system, strengthening your heart, oxygenating your blood, helping your body to metabolise sugar and fat for balanced energy and weight maintenance. Your immune system and neuroendocrine system (hormones) benefit from all of this as they are resourced to function as they should and your hormones are potentially nicely balanced by the increased endorphins and serotonin. Your regulatory systems can in turn positively impact your mood and outlook and capacity for doing things.

There is much research to show that when you experience ongoing hardship, stress, relational issues and trauma, it negatively impacts these regulatory systems, in turn impacting your mental health and physical health [8].

Biochemistry and neurochemistry

To keep you alive and functioning, there are multiple chemical processes going on in your body at any given time. This is what allows the electrical impulses in your brain and nerves. Neurochemicals are the specific chemical substances like neurotransmitters and hormones that are responsible for the communication in the nervous system impacting how you think, feel and act. You may be familiar with dopamine and its association with motivation and reward, endorphins and the association with pleasure and adrenaline and its association with urgency. The truth is there are many different neurochemicals, with differing functions, in different combinations and proportions.

When you have social experiences, or when you have physical experiences, this impacts your neurochemistry, which in turn can further impact your psychological experience. Depending on your emotions, your thought processes, your relationship with your feelings, this can feed into your neurochemistry further, with subsequent effects on your physiology, health and mood.

When you are socialised to a biomedical approach to health, it is natural to feel that your only scope for improving your health is through medical intervention. Of course, medical interventions are fundamental in lots of situations. However, their importance often obscures another fundamental piece of the puzzle that may even determine whether the medical intervention works and to what degree. And that is the role of psychology: what you think, feel and do. Enmeshed with this is also the social and environmental element. If you feel well supported and connected, you are much more likely to have better outcomes than if you feel ostracised and judged [9].

As your reading this you may be thinking ‘wow, ok, but where do I start?!’

And understandably so. There is a lot to be informed about and a lot to unpack, as well as explore in terms of how it is or isn’t personally relevant to you. This is where the suggestion to go to CBT comes in!

While many doctors may not themselves be familiar with the mind body connection and psychobiological processes, they have an understanding that in principal it is important to address the psychological elements of experiencing illness and stress to help people cope. Ideally, the suggestion should be raised sensitively with some clarification of these concepts – which will be discussed further in future instalments. Unfortunately, I know this doesn’t always happen and that can have a massive impact on your sense of readiness for therapy when trying to navigate health issues.

If you’d like to explore how psychological therapy specifically may be relevant to you and your health experiences, you can take the quiz I developed below.

References: [1] R. B. Merkatz, 'Inclusion of Women in Clinical Trials: A Historical Overview of Scientific Ethical and Legal Issues', Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 78–84, Jan. 1998, doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1998.tb02594.x.

[2] K. Donnelly, 'Patient-centered or population-centered? How epistemic discrepancies cause harm and sow mistrust', Social Science & Medicine, vol. 341, p. 116552, Jan. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.116552.

[3] G. M. Hildenbrand, E. K. Perrault, and R. H. Rnoh, 'Patients' Perceptions of Health Care Providers' Dismissive Communication', Health Promotion Practice, vol. 23, no. 5, pp. 777–784, Sep. 2022, doi: 10.1177/15248399211027540.

[4] A. C. Ford, 'Overlap Between Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Inflammatory Bowel Disease', Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y), vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 211–213, Apr. 2020.

[5] 'Interaction between social pain and physical pain - Ming Zhang, Yuqi Zhang, Yazhuo Kong, 2019'. Accessed: May 16, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.26599/BSA.2019.9050023

[6] A. Pichon and D. Chapelot, Homeostatic Role of the Parasympathetic Nervous System in Human Behavior. 2010.

[7] 'Gut feelings: associations of emotions and emotion regulation with the gut microbiome in women - PubMed'. Accessed: May 16, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36942524/

[8] B. S. McEwen, 'Stress, adaptation, and disease. Allostasis and allostatic load', Ann N Y Acad Sci, vol. 840, pp. 33–44, May 1998, doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09546.x.

[9] 'The Connection Prescription: Using the Power of Social Interactions and the Deep Desire for Connectedness to Empower Health and Wellness - Jessica Martino, Jennifer Pegg, Elizabeth Pegg Frates, 2017'. Accessed: May 18, 2025. [Online]. Available:

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1559827615608788