The Role of the Brain in Healing the Body

Jul 3

/

Dr Sula Windgassen

Whether you are without health complaints, dealing with confusing symptoms without a clear diagnosis or have a defined condition with clear structural changes in the body, the brain has a hugely significant role in your health outcomes.

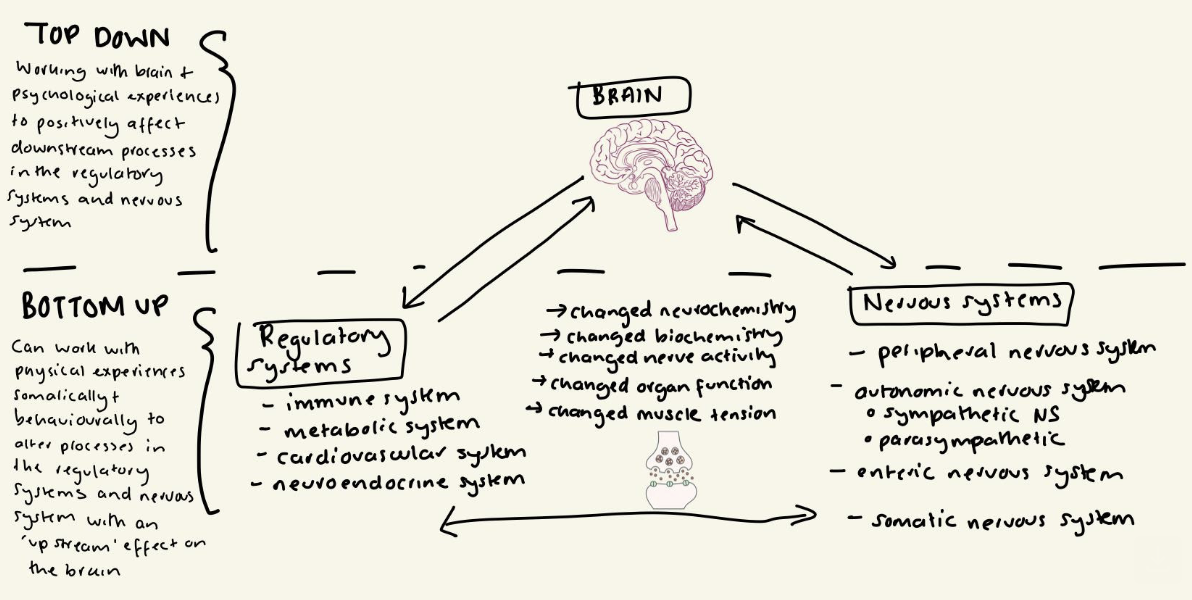

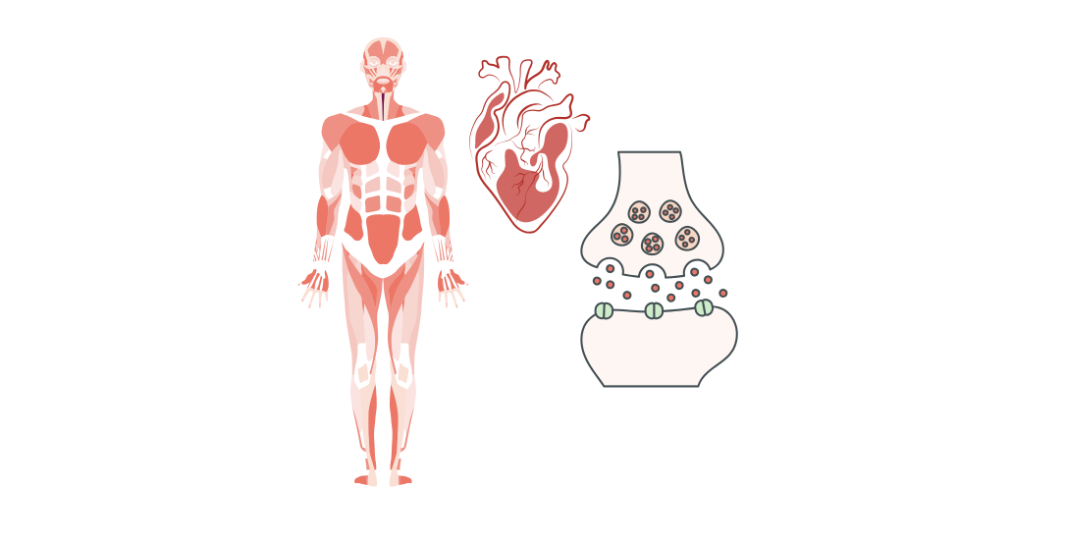

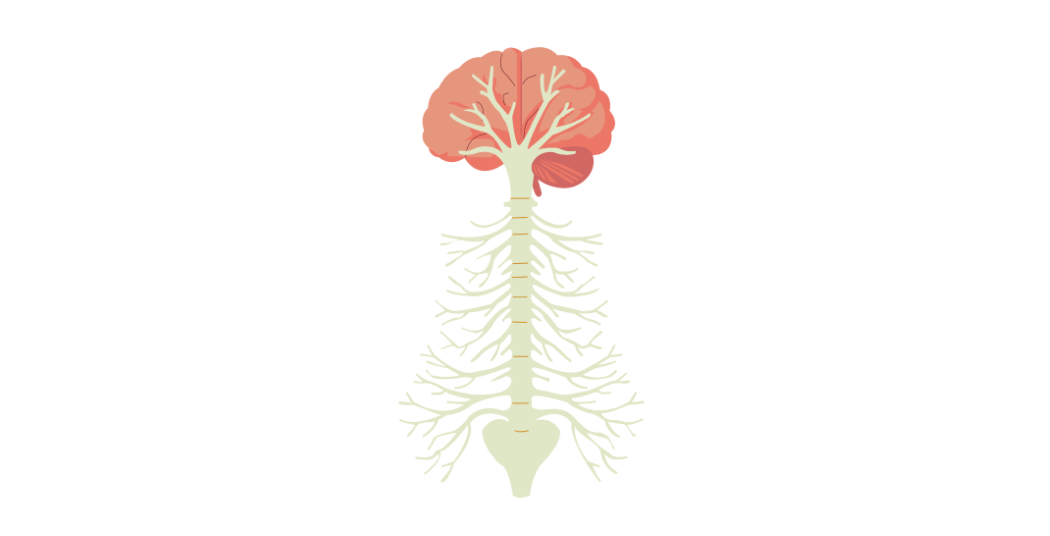

That is because your brain is the central computer that combines all the incoming and outgoing signals that determine what physiological processes take place as well as how you physically and emotionally feel, what you think and do. This is an ongoing process as how you feel (emotionally and physically) constantly updates what is happening physiologically, which consequently updates how you feel and so on. What you think and do, can modify this relationship.

In a previous article, I explained some of the key mind-body (or psychobiological) pathways that are responsible for this two-way communication. At the helm of all of these pathways ultimately is the brain as shown in the image below.

It's not a case of mind over matter

If you feel daunted or resistant to the idea that your brain has a role in your physical health outcomes, that might be because this sort of information is often packed in 'mind over matter' narratives. These messages can tell you that the key to healing is all in your mind (or 'all in your head') and therefore place over-emphasis on your own personal responsibility to 'get better' – whatever that means to you. I find these messages can be inhibitive of truly healing and tend to be very ableist, seeing healing as a coming back to precise ableist standards i.e. having a body that is able to do everything you require of it, namely achieve, push and fit into societal standards that aren't always so healthy.

It's hard because mind over matter narratives also can feel very empowering and hold a lot of truth and evidence. Your brain and psychology truly are powerful and can alter a lot. But this should not be confused with the idea that it then becomes all on you to solve your own health and goals. Human beings are designed to be social creatures, physically requiring co-regulation and practical cooperation from others (1).

Ways your brain can help heal the body

First let's define what we mean by 'healing'. I'm going to use a holistic concept of healing that covers physically and emotionally healing. I like the sentiment from a paper I read on the topic of a clinician's role in healing patients, that talked about healing as a “becoming whole”.

The sentiment of healing here, was there was not a sole fixation on the 'getting rid' of symptoms but on a reestablishing of safeness and security. In line with this I'll use this definition of healing more broadly:

To heal is to connect body and mind, so that you can access safety, meaning and wholesomeness day to day.

When, specifically exploring how the brain can heal the body, we're focusing on how the brain can help resume balance and healthy functioning across body systems with the effect of improving physical symptoms and health outcomes.

Here are the main ways:

Brain regulating immune function

Ground breaking research in the 80's showed that experiencing psychological stress physically altered the immune system, slowing its ability to heal from wounds (2). Since then research has hugely progressed, showing that how you think, what you imagine and what you feel can directly affect the activity of your immune system (3).

This means that nurturing your brain health physically through diet, exercise, emotion regulation and specific cognitive processing work, is hugely important for helping your immune system. There are specific strategies of working with your brain, like using visual imagery that have been shown to physically enhance immune system function (4).

Brain balancing your regulatory systems for homeostasis (body regulation and equilibrium)

In previous articles I've explained a little about the four core regulatory systems that your body has. These help your body keep balanced so that it can restore health when depleted and maintain optimal processing. Your brain is the central hub for these regulatory hubs communicating with each other and liaising with the various branches of your nervous system. When you perceive threat, or lack of control, when you aren't able to regulate your emotions, all of this can deplete your regulatory systems, with a deleterious effect on your long term health (5,6).

This is why working with your perception of stress, your threat appraisals and sense of control is so important to ensure the brain healthily communicates with the regulatory systems (7)

Brain balancing your hormones

Your brain plays a central role in balancing your hormones through one of the regulatory systems, the neuroendocrine pathway, and a specific pathway involved in chronic stress called the hypothalamic-pituitary- adrenal axis. The hypothalamus is the area of the brain that responds to and initiates a whole series of hormonal responses that have effects on all of the regulatory systems and the functioning of organs in the body. Compelling research shows that psychological therapy can have regulating effects on hormonal balance in the context of chronic illness like HIV, with enhancing effects on immune system functioning (8). Cognitive behavioural therapy has even been shown to initiate hormonal recovery in women who no longer have periods due to hypothalamic amenorrhea (9).

Working with your brain for the good of your hormones, means identifying patterns that are taxing your mind and body and interrupting them. This allows you to get back to an equilibrium long term.

Brain regulating your autonomic nervous system

In previous articles, we've considered how your autonomic nervous system, which governs your fight or flight response and the counterbalancing 'rest and digest' response, is impacted by psychological stress and demands. Your brain is the first line instigator of this response as it is the organ that allows you to perceive a stressor and then determine degree of threat and demand required. For this reason, it is important to work with your threat appraisals and the connection between brain and autonomic response, to help down-regulate overly reactive stress responses. Research has shown that it is possible to change the perception of stress, with a positive impact on autonomic activation and even physical symptoms like tension headaches (10).

Brain reducing pain by updating nervous system activity

Advances in pain science have definitively shown that the brain plays a significant role in pain processing, even in so far as it can determine whether you feel pain and for how long. This is because particular areas of your brain including the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), thalamus and amygdala that activate when you experience pain, also activate when you experience emotional pain (11). Studies show that the more heightened negative emotions are, and the more fearful thoughts are about your physical state, the more pain the brain calculates you should feel (12,13).

To help downregulate pain, it is important to work with the emotional aspect of pain and the sense of threat that it represents. This work can physically reduce pain as well as the panic that comes with painful symptoms. You might find the pain booklet helpful to get started.

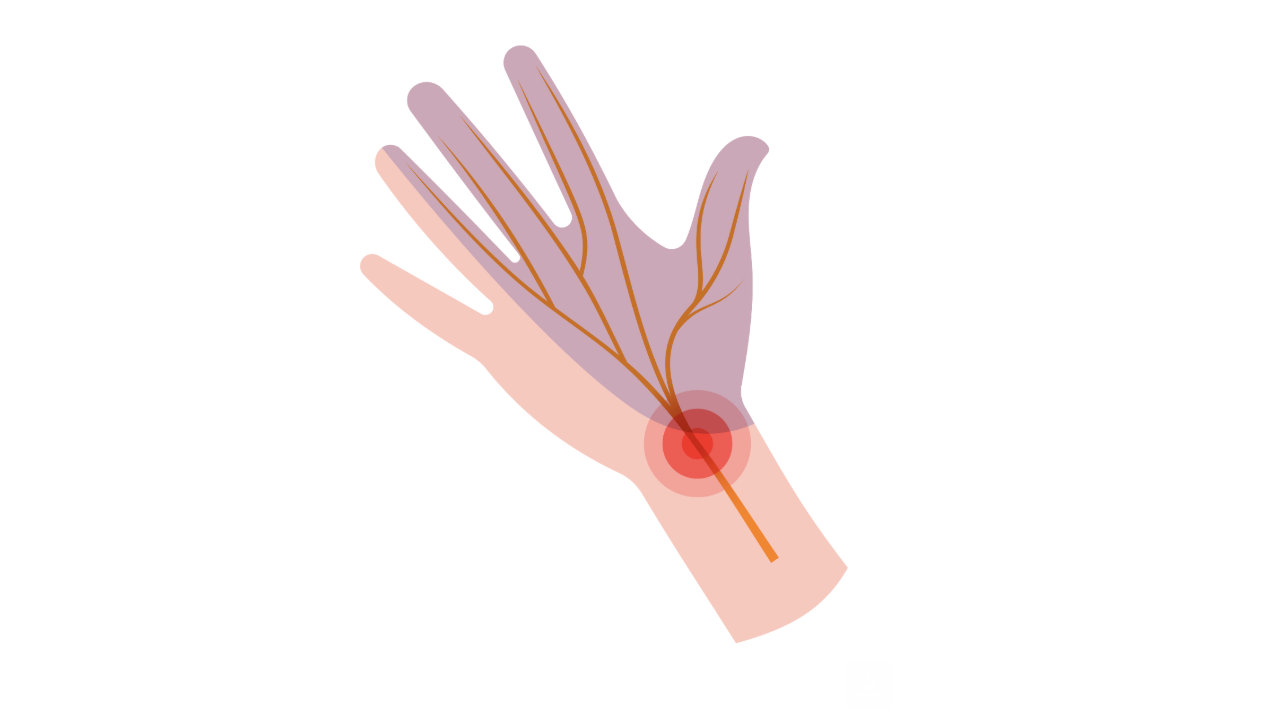

Brain interrupting discomfort and panic at physical symptoms through interoceptive updates

When you are experiencing disruptive physical experiences (e.g. pain, fatigue, dizziness, heart palpitations, tension, gut or bladder issues), this updates how your brain is relating to your body. It starts to see these physical symptoms and the areas related to the symptoms (e.g. particular body parts and organs) as threats. A particular area of your brain that integrates sensory, emotional and contextual information, the insula, then changes the calculations it makes. It can mean that you end up feeling more on-guard against your body and more confused by the sensations you are experiencing. This in turn can heighten anxiety and negative mood states, which can further disrupt calculations. A cycle of physical and emotional dysregulation can ensue as you feel less safe in your body and worse emotionally.

Research shows that interventions targeting interoceptive awareness – interventions that change your body awareness and update how you relate to your bodily experiences – can physically regulate your body, reduce physical sensations and improve health outcomes (14,15).

Working with your brain to improve your health

There are many more ways the brain can shape physical recovery and healing, but this gives a good starting point for understanding. You may be familiar with this fact, but it bears explicitly writing that just because your brain can impact on all of this, it doesn't mean that you always have control over your brain! You don't. far from it. Your brain, like any other organ, is constantly working behind the scenes. Unlike any other organ, it is also constantly making predictions about what is going to happen next, whilst simultaneously processing what is happening now. There is a lot going on.

This means when you want to work with your brain to help heal your body, you have to be realistic and strategic. If the brain is too overwhelmed, it cannot perform for you. Think of an over-heating computer! Everything slows down or even crashes out. Instead, you need to work with the brain and build up skills, it can later expand upon. An understandable assumption people form is that working with the brain happens predominantly through thinking. This generally isn't true. It is through what you do and how you work with your physical and emotional experiences. This creates the foundation for 'thinking to change your brain' to be effective! Let me give you an example. If I realise my immune system is highly reactive and I want to work with my brain on this, I don't simply use imagery to instruct my brain to instruct my immune system. This can work for some – indeed imagery has been an effective way of changing the immune system (4). However, if you don't feel confident in this working, if you are also running 10,000 other decisions and thought processes and you have a hostile relationship with your body, your brain is going to factor all this in. So, you need to do some groundwork to allow the brain to get these results for you.

The first step is building up your interoceptive awareness. More coming on this soon – but in the meantime you might like touse some of the nervous system resources.

The second step is changing the communication between brain and body, building on these interoceptive awareness skills. Ideally this will be tailored to your physical experience of symptoms. If you have fatigue, this will look different to if you have pain or headaches or gut symptoms. If you'd like to get a better idea of what this could look like in practice, you might like to take the quiz I designed. It is comprehensive, so set some time aside.

The third and fourth step involve working on emotion regulation and internal mental habits, which have a massive impact on how your brain is processing things and the sorts of instructions it sends to your body.

Things like therapy, physiotherapy, nervous system regulation, journaling and meditation can help with all of this, but I find from my clinical practice (and the research), having structure and a tailored plan with the opportunity for feedback and guidance helps. That's why I created Body Mind Connect, which has live weekly workshops, a Q&A feature for tailored feedback and an extensive hub of all the information and practices related to this article.

References:

[1] 'Threat, safety, safeness and social safeness 30 years on: Fundamental dimensions and distinctions for mental health and well‐being - Gilbert - 2024 - British Journal of Clinical Psychology - Wiley Online Library'. Accessed: Jan. 31, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/bjc.12466

[2] J. K. Kiecolt-Glaser, W. Garner, C. Speicher, G. M. Penn, J. Holliday, and R. Glaser, 'Psychosocial modifiers of immunocompetence in medical students', Psychosom Med, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 7–14, 1984, doi: 10.1097/00006842-198401000-00003.

[3] J. E. Bower and K. R. Kuhlman, 'Psychoneuroimmunology: An Introduction to Immune-to-Brain Communication and Its Implications for Clinical Psychology', Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, vol. 19, no. Volume 19, 2023, pp. 331–359, May 2023, doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-080621-045153.

[4] E. C. Trakhtenberg, 'The effects of guided imagery on the immune system: a critical review', Int J Neurosci, vol. 118, no. 6, pp. 839–855, Jun. 2008, doi: 10.1080/00207450701792705.

[5] B. S. McEwen, 'Brain on stress: how the social environment gets under the skin', Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 109 Suppl 2, no. Suppl 2, pp. 17180–17185, Oct. 2012, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121254109.

[6] 'Stress of stoicism: Low emotionality and high control lead to increases in allostatic load: Applied Developmental Science: Vol 20, No 4'. Accessed: May 18, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10888691.2016.1171716

[7] A. W. Carrico and M. H. Antoni, 'Effects of Psychological Interventions on Neuroendocrine Hormone Regulation and Immune Status in HIV-Positive Persons: A Review of Randomized Controlled Trials', Biopsychosocial Science and Medicine, vol. 70, no. 5, p. 575, Jun. 2008, doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31817a5d30.

[8] V. Michopoulos, F. Mancini, T. L. Loucks, and S. L. Berga, 'Neuroendocrine recovery initiated by cognitive behavioral therapy in women with functional hypothalamic amenorrhea: a randomized, controlled trial', Fertility and Sterility, vol. 99, no. 7, pp. 2084-2091.e1, Jun. 2013, doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.02.036.

[9] A. Omidi and F. Zargar, 'Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on perceived stress and psychological health in patients with tension headache', Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, vol. 20, no. 11, p. 1058, Nov. 2015, doi: 10.4103/1735-1995.172816.

[10] E. L. Meerwijk, J. M. Ford, and S. J. Weiss, 'Brain regions associated with psychological pain: implications for a neural network and its relationship to physical pain', Brain Imaging and Behavior, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 1–14, Mar. 2013, doi: 10.1007/s11682-012-9179-y.

[11] K. Wiech and I. Tracey, 'The influence of negative emotions on pain: Behavioral effects and neural mechanisms', NeuroImage, vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 987–994, Sep. 2009, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.05.059.

[12] T. Jackson, Y. Wang, and H. Fan, 'Associations Between Pain Appraisals and Pain Outcomes: Meta-Analyses of Laboratory Pain and Chronic Pain Literatures', The Journal of Pain, vol. 15, no. 6, pp. 586–601, Jun. 2014, doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.01.499.

[13] M. Datko et al., 'Increased insula response to interoceptive attention following mindfulness training is associated with increased body trusting among patients with depression', Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, vol. 327, p. 111559, Dec. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2022.111559.

[14] D. J. Edwards and T. Pinna, 'A Systematic Review of Associations Between Interoception, Vagal Tone, and Emotional Regulation: Potential Applications for Mental Health, Wellbeing, Psychological Flexibility, and Chronic Conditions', Front. Psychol., vol. 11, Aug. 2020, doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01792.

The sessions help me to better understand how concepts apply to me and my illness/experience, and how I can use this knowledge to inform my recovery. It is also extremely validating to be with a group of people that understand and feel similar. The sense of community helps me to feel less alone with a condition that is very isolating."

Body mind connect member

About Dr Sula Windgassen, PhD

Dr Sula is a Health Psychologist, Cognitive Behavioural Therapist, Eye Movement Desensitisation & Reprocessing (EMDR) Therapist and Mindfulness Teacher. Trained at King's College London & publishing papers on the use of psychology to improve health and whole-person wellbeing.

Featured links

Copyright © 2025